KCNT1 Genetic Testing: Genetics 101 for Families

Understanding the fundamentals of genetics and genetic testing for families affected by rare conditions.

Understanding Genetic Testing for KCNT1

KCNT1-related conditions are caused by changes in the KCNT1 gene, which plays a key role in controlling electrical activity in the brain. These conditions are only diagnosed through genetic testing—they cannot be identified by physical exams, imaging, or routine lab tests. Many families first learn about genetic testing when a child experiences seizures or developmental delays, prompting doctors to order a seizure gene panel or broader tests like whole exome or whole genome sequencing (WGS). Testing may include both parents to help determine whether a genetic change is inherited or de novo (new in the child).

KCNT1-related conditions can follow an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning a change in just one copy of the gene can cause symptoms. Sometimes, the variant is inherited from a parent, while other times, it arises spontaneously (de novo)—appearing for the first time in the child. Importantly, not all changes in the KCNT1 gene cause disease; some variants have no effect on health. Genetic testing helps distinguish between harmful (pathogenic) variants and those that are likely benign, which is essential for guiding medical care, treatment decisions, and family planning.

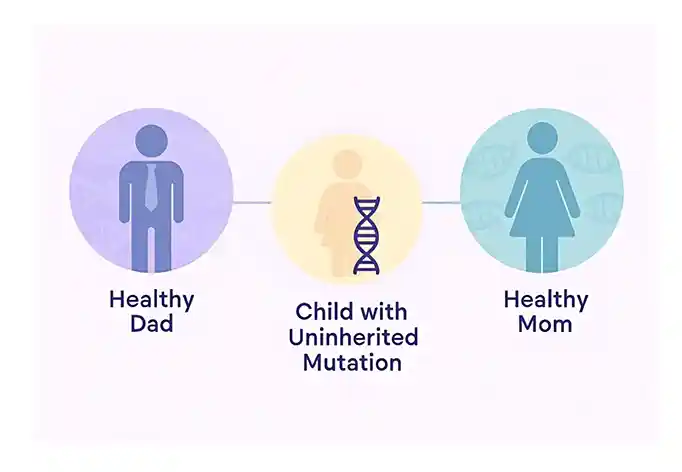

What is a de novo variant?

A de novo variant is a change in someone’s DNA that newly appears in a family. This usually happens when there is a change in the DNA in the sperm or egg cell prior to conception.

It can also occur as a result of a DNA change very early during development in the womb. De novo variants happen randomly, meaning there is often no identifiable cause other than chance, and there is no way to prevent it.

When a child is born with a de novo variant, the chance of the same variant happening again in future pregnancies is typically very low. However, in rare cases, a parent may have germline mosaicism, which can increase the recurrence risk.

What is Mosaicism?

Most of our cells carry the same DNA sequence, inherited from the first cell formed after the sperm and egg combine. This single cell divides repeatedly to form the developing baby.

Sometimes during these divisions, the DNA is copied incorrectly, causing some of the cells to have a genetic variant not seen in the rest. This difference is called mosaicism.

There are two main types of mosaicism:

- Somatic mosaicism The variant is found in some of the body’s cells (e.g., skin, muscle, or brain), but not in the sperm or egg. It usually does not affect future children.

- Germline mosaicism The variant is present in some sperm or egg cells. A person may have no signs of the variant themselves, but it can be passed on to their children.

Germline mosaicism is difficult to detect and is usually only suspected when multiple children are affected by the same condition without it being present in the parents’ blood DNA.

How is germline mosaicism different from a de novo variant?

De Novo Variant

The genetic change typically occurred in a single sperm or egg cell, so the chance of it happening again is usually very low.

Germline Mosaicism

The parent may have multiple sperm or egg cells with the same variant, so the chances of recurrence may be higher, depending on how many cells are affected.

Both germline mosaicism and de novo variants can explain why a child is born with a genetic condition that hasn’t been seen in the family before.

Germline mosaicism is rare and often cannot be confirmed through standard genetic testing.

If you have questions about de novo variants or recurrence risk, it’s important to speak with a genetic counselor or medical geneticist.

Family Planning: Options for Prenatal Testing and Genetic Counseling

If you have a known KCNT1 mutation or are concerned about passing on a genetic condition, several family planning options are available to help you make informed decisions.

Amniocentesis and Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS):

These are prenatal tests that can diagnose genetic conditions in a fetus during pregnancy. Amniocentesis, usually performed between 15 and 20 weeks, involves taking a sample of amniotic fluid surrounding the baby, while CVS is typically done earlier, between 10 and 13 weeks, to obtain a sample from the placenta. These tests can help identify if a fetus carries the KCNT1 mutation, allowing families to make decisions based on this information.

Germline Mosaicism vs. De Novo Variants:

- De Novo Variant: This occurs when the genetic change happens in a single sperm or egg cell, so the chance of recurrence is usually very low.

- Germline Mosaicism: In this case, a parent may have multiple sperm or egg cells with the same variant, which increases the chance of recurrence. Germline mosaicism is rare and may not always be detected through standard genetic testing.

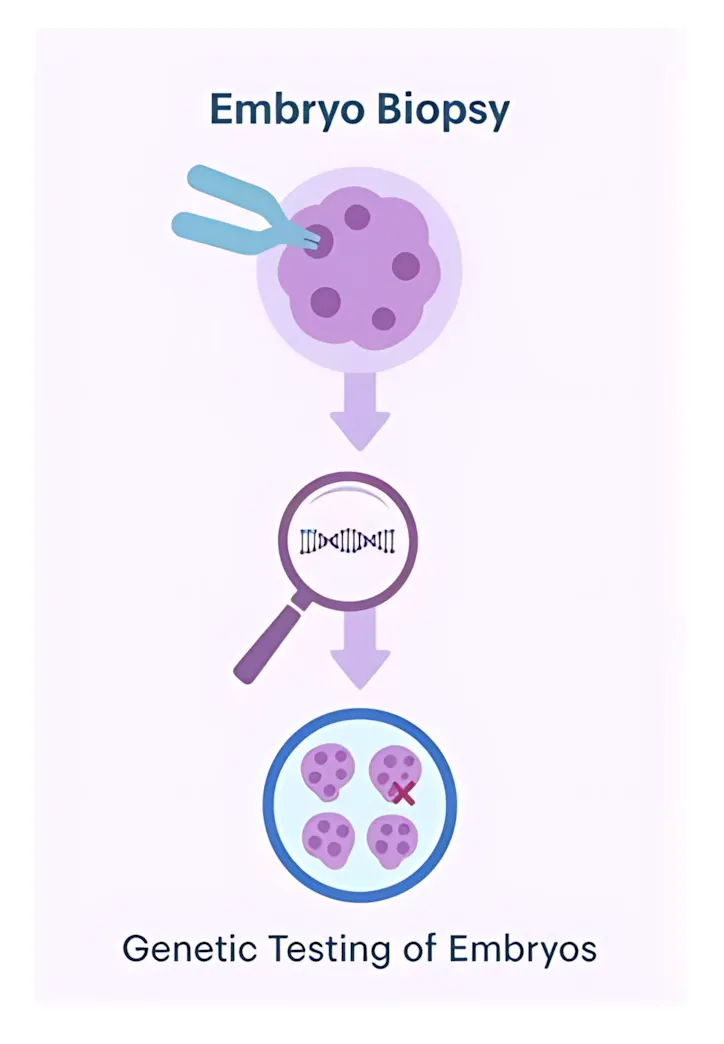

PGT-M (Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Monogenic Conditions):

PGT-M can be an option for couples with a known genetic condition, like KCNT1 mutations, who want to reduce the risk of passing the condition to their child. The process involves IVF (in vitro fertilization) to create embryos, which are then tested to identify those that do not carry the genetic condition. While PGT-M can help select embryos at lower risk of inheriting the condition, it only tests for known variants and does not guarantee a healthy child.

Important Considerations for PGT-M:

- It only tests for known variants.

- It doesn’t guarantee the child will be unaffected.

- The process is time-consuming, expensive, and may require multiple IVF cycles.

If you’re considering PGT-M, consult a genetic counselor trained in reproductive genetics.

What is a VUS?

A VUS (Variant of Uncertain Significance) is a change in your DNA whose effect on health is not yet understood.

Our DNA acts like an instruction manual, made up of four chemical “letters”: A, T, G, and C. Everyone has thousands of natural spelling differences—called variants—that make us unique. Most of these are harmless or even helpful. Some are known to cause disease and are labeled pathogenic.

But sometimes, a genetic test finds a variant that doesn’t have enough evidence to be clearly classified as either harmful (pathogenic) or harmless (benign). These are called variants of uncertain significance (VUS).

Can a VUS classification label change over time?

Yes. As more people are tested and more research becomes available, labs may reclassify a VUS as either pathogenic (disease-causing) or benign. This process can take months or even years.

What your doctor may recommend

- Regular updates from the testing lab

- Testing other family members, which can help clarify the variant

- Submitting your results to variant-sharing databases (like ClinVar)

Why reclassification matters

Most clinical trials and gene-specific treatments—including those for KCNT1-related conditions—require that a variant be classified as “pathogenic” or “likely pathogenic” in order to be eligible. If your variant is still a VUS and you believe it could be the cause of your or your child’s condition, speak with your doctor or a genetic counselor about what steps can be taken toward reclassification.

What is a Genetic Counselor?

A genetic counselor is a healthcare professional with specialized training in genetics and counseling.

Medical History

Help you understand your personal and family medical history

Testing Options

Explain genetic testing options

Family Planning

Discuss family planning and risk assessment

Decision Support

Support you in making informed decisions

You can ask your doctor for a referral or find a certified provider through the National Society of Genetic Counselors directory.

How to Get a Copy of Your Child’s Genetic Test Report

Parents of children with KCNT1-related epilepsy often need a full copy of their child’s genetic test report. This report confirms the exact KCNT1 variant and is important for medical care, research, and future clinical trial eligibility.Why you need the full genetic report

You will need the complete laboratory report to:

- Prove your child has a KCNT1 diagnosis for clinical trials.

- See whether your child’s KCNT1 variant has been reclassified since the original test.

- Share accurate information with neurologists, geneticists, and epilepsy specialists.

- Join KCNT1 registries and research studies.

- Understand how the KCNT1 variant may relate to your child’s seizures and development.

KCNT1 science is changing quickly. Some variants that used to be reported as “Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS)” are now known to be likely pathogenic (LP) or pathogenic (P). This can change care and may open the door to new treatments or trials.

How to get your child’s genetic test report

1. Start with what you remember

Even if the test was done years ago, try to recall:

- Which doctor ordered it (neurologist, geneticist, NICU doctor, pediatrician).

- Which hospital or clinic you were at.

- Roughly when it was done (month or year).

- Why it was ordered (seizures, NICU stay, EEG changes, developmental concerns).

2. Contact the doctor who ordered the test

This is usually the fastest path. Call the office and say:

“I would like a full copy of my child’s genetic test report, including the detailed KCNT1 variant and interpretation.”

Good places to start:

- Your child’s neurologist or epileptologist.

- A clinical geneticist or genetic counselor you saw.

- The NICU team (for very early-onset cases).

- Your child’s pediatrician (they may have a copy in the chart).

3. Ask the hospital or clinic’s medical records department

If you don’t remember who ordered the test, contact the hospital or clinic and ask:

“I am requesting a complete copy of my child’s genetic test report from your records.”

Most hospitals can send reports through a patient portal, secure email, or postal mail. Some may ask you to sign a release-of-records form.

4. Contact the genetic testing laboratory

If you know which lab performed the test (for example GeneDx, Invitae, Ambry, Blueprint, Labcorp, Prevention Genetics, ARUP), you can ask them directly for the report.

Say something like:

“My child had a genetic test through your laboratory. I would like a copy of the full report. What information do you need from me?”

They may ask for your child’s name, date of birth, the ordering doctor or hospital, and the approximate date of testing.

5. If you live outside the United States

Access to reports can vary by country, but parents can usually still obtain a copy. Some tips:

- Contact the original hospital or clinic’s records or medical records office.

- In some countries, the laboratory will only release the report to a doctor. In that case, ask your neurologist or pediatrician: “Could you request a full copy of my child’s genetic report from the lab?”

- If you have moved to another country, email the original hospital to request an international release of records.

Always ask specifically for the full diagnostic laboratory report (PDF), not just a short summary letter.

Variant reclassification and why it matters

As more KCNT1 patients are identified and more research is done, labs often review and update their interpretations of specific variants. This is called variant reclassification.

A variant can be reclassified, for example, from:

- VUS (Variant of Uncertain Significance) → Likely Pathogenic (LP)

- VUS → Pathogenic (P)

- Likely Pathogenic → Pathogenic

When a variant is reclassified, it can affect:

- How clearly KCNT1 explains your child’s seizures and other symptoms.

- Eligibility for KCNT1-specific clinical trials and research studies.

- Access to services, insurance coverage, and support.

- Genetic counseling and future family planning decisions.

This is why it is important to know whether your child’s KCNT1 variant has been reviewed recently and whether a newer report is available.

How parents can ask for a reclassification review

If your child’s report lists the KCNT1 variant as “uncertain” (VUS) or you’re not sure what the classification means, you can talk with your child’s neurologist or geneticist about requesting a re-review.

You might say:

“We believe this KCNT1 variant may be causing our child’s seizures and health problems. Can you send updated clinical information to the testing lab so they can consider reclassifying the variant?”

The doctor can share with the lab:

- Seizure types, frequency, and EEG findings.

- Developmental history and neurologic exams.

- Brain imaging (MRI) findings, if available.

- Response to anti-seizure medications and other treatments.

- Parental and family genetic testing results.

The laboratory then re-evaluates the variant using professional guidelines and may issue a new report if the classification changes. This updated report can be important for clinical trial applications and future care decisions.

What a complete genetic report should include

A full KCNT1 laboratory report typically includes:

- The gene name: KCNT1.

- The exact variant written out (for example: c.1283G>A; p.R428Q).

- The current classification (pathogenic, likely pathogenic, VUS, likely benign, or benign).

- Whether the variant is de novo (new in the child) or inherited.

- A written interpretation and explanation of the evidence.

- Any recommendations for follow-up or family testing.

If you receive only a short clinic letter, ask specifically for the full diagnostic laboratory report (PDF).

Need support getting or understanding your report?

The KCNT1 Epilepsy Foundation can help families:

- Understand which parts of the genetic report are most important.

- Figure out what might be missing and how to request it.

- Prepare questions for your neurologist or genetics team.

- Learn how KCNT1 variants may relate to clinical trial readiness.

- Connect with registries and research opportunities when appropriate.

If you are unsure where to start, reaching out for support is a helpful first step. You do not have to navigate this alone.

FAQS

Q: What’s the chance of having another child with the same KCNT1 mutation?

In this scenario—a de novo variant in KCNT1—the chance of having another child with the same mutation is typically low, but not zero.

Here’s why:

- Most de novo mutations happen by chance in a single egg or sperm cell. That means they’re not present in the rest of the parent’s body.

- However, some parents may have germline mosaicism, where a small number of their sperm or egg cells carry the mutation, even though it doesn’t show up in their blood test. This is rare, but it can increase recurrence risk.

Estimated recurrence risk:

- Usually <1%, but

- Can be higher (up to 5–10%) if germline mosaicism is suspected (especially if more than one child is affected or there’s a strong family history).

What to do:

- Speak with a genetic counselor or medical geneticist.

- They may recommend additional testing or a careful discussion of PGT-M (preimplantation genetic testing) if you’re considering future pregnancies.